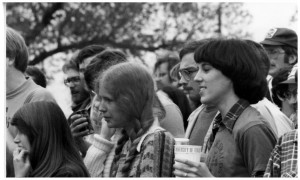

Judge Jean Shepherd, L’77, was one of the KU Law women pioneers of the 1970s. Like several of her women classmates, Shepherd pursued law as a second career, leaving behind the fields traditionally open to women at the time. When she entered law school in 1974, Shepherd was a non-traditional student, a single mother and a former high school teacher. The campus had changed since she completed her undergraduate degree in 1968. Women were wearing jeans to class, and students were consumed with the Vietnam War and civil rights, which resulted in a more “aware and involved” student experience.

“I graduated in January of 1968,” Shepherd said. “Things were really changing on campus. When I was an undergrad the big ruckus was women not wearing dresses to class. Those were such non-issues when I came back for law school in 1974. Students were focused on larger issues. We were much more aware of the world and the country. It was no longer this idyllic, Midwestern isolated college experience. It was much more aware and involved.”

Though the atmosphere on campus was one of engagement and action, the KU Law community was still adjusting to women studying in Green Hall. “We had a little bathroom with just two stalls, and there would always be a long line coming out the door,” Shepherd said. “It wasn’t set up for women students at that point.”

Aside from the logistical issues, more fundamental challenges existed as well.

“I was a single parent,” Shepherd said. “I found out we were expected to have Saturday classes. I didn’t have child care. I went to Martin Dickinson, gathered all my courage, and said, ‘I don’t have day care for Saturday classes and can’t make that work.’ He rearranged my schedule, which was unheard of. But that was it for me. It meant I was able to stay.”

Shepherd and her women classmates banded together to tackle the challenges, developing deep friendships, professional connections, and a spirit of camaraderie and cooperation that continues today.

“I just remember how close the women in my class were, and it certainly wasn’t because we all had similar interests,” Shepherd said. “There was a woman who was a harp major and sold real estate, a woman who was a nun, women from a variety of first careers. There were not a lot of us, but we were really close. We ate lunch together and encouraged each other. It took that kind of a process for us to feel comfortable enough to stay there and get through it.”

Though she left teaching behind, Shepherd maintained her commitment to children and families throughout her law practice and judicial career.

“I always valued areas of the law that related to children and families and thought that’s where a difference could be made for the future,” Shepherd said. “In law school I was head of the juvenile clinic, and we represented children in court. When I first started practicing, I was in the DA’s office, so I prosecuted cases involving child victims. When I was in private practice I represented children and families in abuse and neglect cases. In those situations you have one or a few clients and can really advocate for and get to know them. As a judge you’re not an advocate for a child, but I could advocate for system changes and programs that would help children and families involved in the courts system.”

Shepherd also credits her teaching background with making her a more effective judge.

“I think teaching was the best training I had for being in control of a courtroom,” Shepherd said. “There’s a lot of teaching that goes on–explaining people’s rights and the process. There’s a look that students and adults get when they’re nodding their heads but don’t understand. You need to recognize that look and rephrase things, find other words to use so people can get some clarity. Sometimes the excuses people use are like all those excuses for why homework didn’t get done, only at a different level.

“In teaching, you learn how to act like you’re in charge even though you’re not sure you are, and there were certainly moments like that in the courtroom. You make really important decisions and you mete out consequences that are hopefully appropriate, but people have to understand the process. If people feel they’ve been heard and if they feel they understand what happened, there are very few complaints.”

– A version of this post appeared in the fall 2015 issue of KU Law magazine. The issue celebrated the career of Martin Dickinson, KU Law’s longest-serving professor, and included reflections from several of Dickinson’s former students.